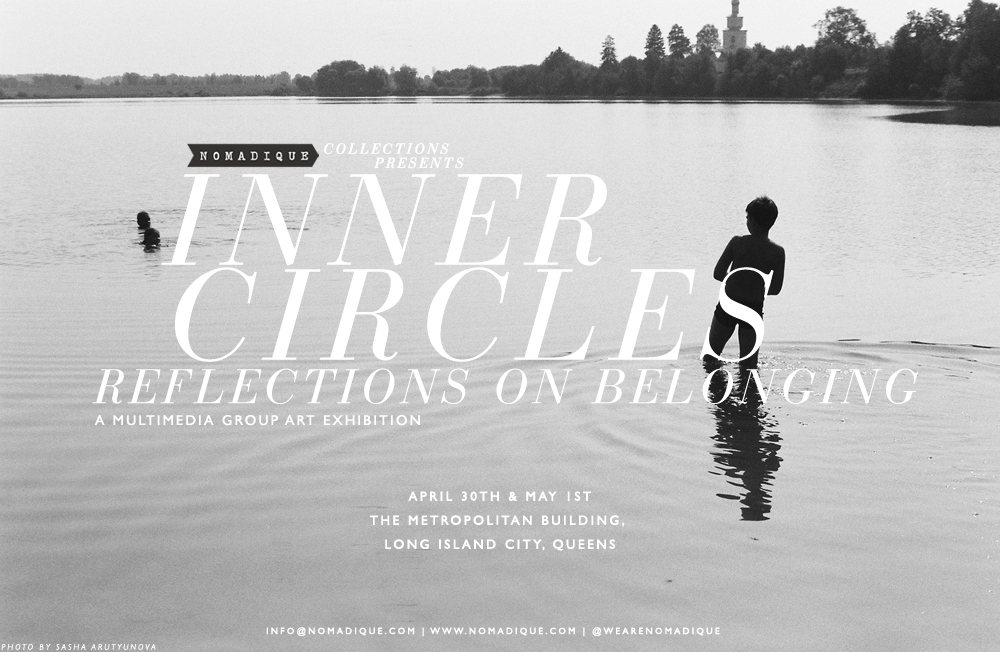

To what do we belong and why? How does an anxiety of belonging impact our development and behavior? How does belonging affect our sense of purpose? Does belonging necessitate exclusion by nature?

Inner Circles: Reflections on Belonging is a two-night pop up art exhibition which invites attendees to explore the many complexities of belonging through the eyes of over a dozen contributing artists. As viewers wander the corridors of the Metropolitan Building, they’ll encounter artworks and reflect on the inner workings of this existential need.

One cannot choose to belong to a given group or community; belonging necessitates both an invitation from the outside and an assent from within. We can love someone without their consent, but we cannot belong without their agreement. This complex dynamic is part of what makes belonging central to our home and family lives, our national and cultural identities, and our religious and spiritual beliefs.

Lifetimes of choices challenge us to pick sides, but how we negotiate the bounds of our belonging—both from the cultures we inherit and the those we adopt—is a personal process that carries universal implications. Ultimately, the decisions we make will shape our stories, our communities, and the legacies we leave behind.

In this year’s exhibition, we invite audiences to find themselves in the reflection and to challenge themselves to consider the complex currents that define our identities—both together and apart.

Featuring Artworks by: Jordan Reznick, Sebastian Collett, Joseph Rodriguez, Emiliano Granado, Irina Rozovsky, Martha Fleming-Ives, Danila Tkachenko, Christopher Cappoziello, Sasha Arutyunova, Mark Davis, Jonno Rattman, Ben Stamper, Ora DeKornfeld, Shane Slattery-Quintanilla, Anatoli Ulyanov, Lindsay Branham & Jon Kasbe

& Performances by: Big Thief, Zusha, Shelley Thomas, Twain, Kenyon Adams & Adam Wade

THE EVENT

FILM SELECTIONS

PHOTOGRAPHY

During my first summer in New York, I discovered Prospect Park as a place to hide from heat, noise, and cement. One afternoon, I took a small motorboat around the lake that sits in the southern end and from that floating perspective, the park revealed itself. Tucked into nooks among the trees on the shore were families, friends, lovers, a myriad of ethnicities, cultures, and religions, all sharing the same land and air for a languorous moment. Here was a perfect modern day realization of Olmstead’s vision for an equalizing space.

My ongoing series In Plain Air depicts the park as a peopled landscape of the mind. Each visitor, escaping the city streets, projects his own geography onto Olmstead’s nineteenth century idyll. And part of the park’s magic is its malleability, the way it responds to individual hopes and collective reverie—its trees and pastures creating a protean backdrop to a complex social reality.

These photographs seek to capture the interplay between city and nature, between human and landscape, and portray the urban oasis in which Brooklynites, hoping for peaceful release, inadvertently play a role in the story of the American melting pot.

In "We Wish that We All Have a Wonderful Life", I place my own desires, suffering and conflicts into the act of photographing my family, sensing how we live in the thrall of our relationships in such a way that our perception of ourselves is profoundly shaped by social realities. It is often difficult for me to know where I end and another begins. At the same time, those that are closest to me are also impossibly far away. It is in this illegible space of being apart together that I photograph.

Whenever I return home to Western Pennsylvania, I continuously photograph my experience. Through documenting symbols and traditions I am working toward a deeper understanding of America, our collective disillusionment in knowing what it once stood for, and where it is going. The photographs are not condemnations but rather acknowledgements that question the traditions and rituals in which we act out, both publicly and privately, our sense of belonging.

Borders, in reality, are merely lines drawn on maps. These lines are constantly shifting depending upon the conditions and people on either side. The border between Mexico and the United States is one such shifting line. Migrant workers are constantly pushing these lines trying to get into the USA to make money for their families' by working on American farms.

Migrant workers follow the seasonal trail from their homes in Mexico, across the border and up into the United States, perhaps starting in California to pick strawberries, then winding through to Arkansas to work with the tomato crop then onward to North Carolina to harvest tobacco. These people are moving, constantly moving, migrating through the country, earning their living and providing an invaluable service to the American farmers. These people represent the 'New Americans,' they are changing themselves through their experiences here, changing their families, changing the face of the USA, even if they aren't citizens. Most Americans don't notice the dusty Mexicans huddled on the street corner getting picked up by trucks, they don't look in the fields to see the Mexicans planting, digging, picking and harvesting, all they are aware of is the fruit they can buy in the market and the cigarettes they can smoke.

The controversy about migrant workers revolves around border security, lost American wages and safety. American workers cry out that Mexican migrant labor steals jobs since the Mexicans will undoubtedly work for lower wages. In fact, most American workers will not deign to labor on farms, harvesting difficult crops like cotton and tobacco whereas Mexicans will do virtually any job. Many farmers have been questioned about what happens if the migrant workers don't come or if the government makes it too difficult for the migrant workers to cross over and they reply that they would shut down without them. Federal government attempts to regulate migrant labor and stipulates that the employer must pay wages, in excess of the federal minimum, which is $4.45 per hour, and are exempt from paying federal tax, social security or state tax. Of course this is assuming the workers have the necessary government approval, likened to a temporary working visa. Most of the migrant workers take their chances crossing the border, usually with the help of a 'coyote' to improve the possibility of success.

These migrant workers have come under public scrutiny lately due to the tragic events, which have led to so many unnecessary deaths. In Wellton, Arizona on May 24th at least 14 Mexicans were abandoned in the desert with minimal water and no hope of ever surviving. The temperature reached almost 115 degrees and they were told to head north until they found the highway - which was about 70 miles away. This was a coyote-run smuggling operation. A coyote, is a person who rounds up those who want to cross the border, takes the money and organizes the trip.

Coyote's often work within a local village and recruit potential migrant workers. The cost varies but most report it to be about $1200. The coyote packs all the migrants into trucks or vans and makes an attempt to cross a border, which usually involves walking for miles through the desert, which can last days until the truck comes and they are driven to a farm or other location.

There are many risks involved but most migrants make the choice since there is no money and few jobs in Mexico. These migrants are sending home about $300 each month which has a higher value in Mexico, sometimes more if working in a restaurant or a shop. Migrant money is worth more than Mexico’s tourist industry, bringing in 5 billion dollars a year.

Like the migratory birds, faithfully succumbing to tradition and instinct, flee the winter in pursuit of temperate climes, so does the New American follow the path laid before him to seek out a living and thus create a new identity in both worlds. (1995-2006)

I was traveling in search for people who have decided to escape from social life and live all alone in the wild nature, far away from any villages, towns or other people.

The main characters of my project violate social standards for different reasons. By a complete withdrawal from society they go to live alone in the wild nature, gradually dissolving in it and losing their social identity. While exploring their experience, it is important for me to understand if one is able to break free from social dependence and get away from the public to the subjective - and thus, to make a step towards oneself.

I am concerned about the issue of internal freedom in the modern society: is it at all reachable, when you’re surrounded by social framework all the time? School, work, family - once in this cycle, you are a prisoner of your own position, and have to do what you're supposed to. You should be pragmatic and strong, or become an outcast or a lunatic. How to remain yourself in the midst of this?

I grew up in the heart of the big city, but I’ve always been drawn to wildlife - for me it's a place where I can hide and feel the real me, my true self, out of the social context.

I believe that in photography there is a redemptive quality. As a medium, it can take that which is ugly and make it beautiful; not by misleading anyone, but by allowing the viewer to stop and look more deeply at the subject. Through this process, the moment becomes distinct; this is where photography lives and breathes. As a photojournalist, my approach to making pictures is not something new or incredibly deep – it is simply to tell the truth. After I become aware of a person’s story, I try to find the visual tools to translate that story as truthfully as possible.

As a photojournalist, I ask the permission of others to be allowed into their lives, to ask questions, to make pictures, in order to learn something that is outside of my own experience. Our society is quite insular in terms of how much we are willing to see beyond our own lives, and how deep we are willing to go. Problems do exist – people suffer from illnesses that are easily treatable, but have no access to the proper medicine, wars are fought and people die, racism continues. We must ad- dress these issues, and I believe that photography can be a part of that process.

Many Americans are marveling that Barack Obama has risen to become the first African American President in a country that has taken a slow and painful path to rid itself of racism. Half a century ago President Obama would have been forced to sit behind the whites in the back of a bus, and forbidden from eating at many restaurants. There is no disputing this history, for many who have lived through that tell their stories today. We are only at this point now because people became deeply involved with asking questions, and then they acted on those questions. I believe to be fully engaged in life means to never stop asking questions of ourselves and of others.

Before you is a collection of photographs, which were first taken by circumstance, while I was cov- ering a story in South Mississippi, during the summer of 2002. They will be an example of hatred to most, and will stir up a great deal of animosity. Many who look at these pictures have expressed feelings of superiority over the people in them because they feel that they are better evolved in their thinking. This is not he purpose of the pictures, it is to learn, and it is to ask questions of how and why racism continues today.

Being a witness to the stories around us, and awakening awareness are among the most important things I can do as a photographer.

Every year the best young cowboys and cowgirls gather in Abilene, Texas for the Youth Bull Riding World Finals. They range in age from 8 to 18 years old. The youngest ride sheep in a sport called Mutton Bustin’ and the oldest ride bulls.

The rodeo was an incongruous mix of sounds, with the howling of cows and boys, the bleats of sheep, and pep talks and one-upsmanships. Bulls snorted and slammed hard against the metal gates separating the chutes as riders rosined their gloves with a sticky slap of leather. Dust rose into the air and men spat soupy tobacco to the dirt floor. There was an eternity of preparation for an 8-second–or often much shorter–ride.

Meatheads, cheerleaders, dudes grinding, a 50

year old lurker hiding-out behind a tucked-in tee shirt and khaki shorts and

floppy fishing hat and a 300mm zoom lens, Baseball caps, hips and toes and lips and fuck yeahs and horns and

thumbs up, basketball shorts past the knees, red necks and zinc noses,

cotton boxers riding up, drinks lots of drinks in sixteen ounce party cups;

translucent green, hot pink and fluorescent orange, all writhe and twist and

wade and pop-off and scream and the tee-shirt dude slash stage hand dude who

works at the club in his goatee and cargo shorts and nike air maxes gives us all a big WHAT’S UP YO LET ME

HEAR IT and we get wilder for him while he slices up edward scissors hand

style brand new wife beaters on the spot for this round of ten girls bang bang bang just like

that. WOOOO HOOOOO.

Growing up gay in a small college town in Ohio, I lived suspended in a state of perpetual yearning. Visions of the life I desired surrounded me like a mirage, but they seemed always just out of reach. Twenty years later, a grown man yet still full of longing, I returned for my high school reunion.

Photography provided a tool for time travel. As I walked those familiar streets, I felt awakening inside me the boy I had been, and the boys I had longed to be. They were still living, but frozen in time – trapped in the body of a man twice their age. The experience was surreal – at once disturbing and awe-inspiring.

Immersed in the landscape of my youth, I found myself scouting for “stand-ins” for characters from my past. Archetypal figures appeared: those I had wanted, or wanted to be – and those I was afraid to become. Looking into their eyes, I encountered my alternate selves. As they met my gaze, I saw them look forward

to their own aging with a mixture of curiosity and trepidation.

We stood at a crossroads; each of us perched on the cusp of becoming the other. Holding my camera, I watched for moments of transition, when the subject seemed on the verge of becoming or vanishing. I photograph to describe these liminal states – evoking the eternal quest to situate the self in time.

The Waking Hours is a series of intimate portraits that documents the life of my father. As a minister, my father spent 34 years devoted to a life of faith and community leadership. Six months before his retirement, however, he quietly fell into a deep sadness. The uncertainty of setting forth into a diminished role - no longer leader of a large community and no longer safely within middle age-provoked a deep crisis within him. Once proud and stoic, he became fragile and childlike, almost unrecognizable. I began to photograph him as a way to understand this transition and to try to construct a new relationship.

Recording some events while staging others, the photographs became a way for me to explore the new man my father was becoming. Furthermore, the act of photographing him allowed me to intimately examine what happens to a man who had dedicated his life to forging an identity that then changes.

INSTALLATIONS

MUSIC

Performances by Big Thief, Zusha, Shelley Thomas & Twain

STORYTELLING & POETRY

Performances by Kenyon Adams & Adam Wade

Caught between the incessant nagging at school and a toxic environment at home, Tyesha has never really felt like she fit in anywhere. When she was sexually assaulted, she felt like she didn’t even belong in her own skin.

But when an alternative spoken word class came to her high school, she learned how to put her struggles into words.

Video, sound & edit by Ora DeKornfeld

Music by Chris Zabriskie

Special thanks to Sacrificial Poets